Brooding is the most important time in a bird’s life, so make the most of it

Recognising the key elements of achieving success from the first day in broiler cycle was the focus of Cargill’s recent poultry workshops, in collaboration with Slate Hall Veterinary Services and Aviagen.

Aviagen’s broiler specialist for UK and Northern Europe, Kieron Daniels, stressed the importance of the early days and on the importance of ‘controlling the controllables’ to get the best out of the birds.

“There are things that matter – like hatchery conditions, chick quality, breeder flock age, and transport – which the farm manager has no influence on. But they can control the farm’s management,” he said, pointing out that all these factors impact on the brooding stage of a chick’s life. “This is the most important stage of the bird’s life, and good gut development and growth now will have a lasting impact on flock performance.”

To achieve this relies on creating the right environment combined with good management. “Feed, air, water, lighting and temperature are all in the mix.”

He drew on extensive data analyses that showed that every 10g increase in chick weight by day 7 added between 40g and 60g of extra weight at day 35, as shown below.

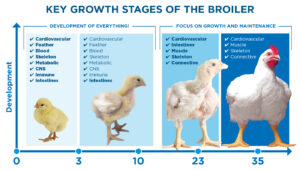

The bird develops most of its systems during the first 10 days post hatching, including the metabolic pathways and the immune system. After this period, the development of these is either finished or, in the case of gut development, slows down.

Muscle development then takes over, as well as the supporting structures such as cardiovascular and skeletal systems, from day 10 to day 35. This is shown below.

“This is why days zero to day three are so important, and when growth must be encouraged, to get the birds off to the best possible start,” he added. “Most growth of the gut wall cells and villi are in the first four days, and this facilitates nutrient absorption and digestibility.

“A poor brood has been shown to impact on villi length and width and muscle thickness, which compromises their function and leaves the gut more prone to infection and less able to absorb feed optimally. And if villi are damaged, they won’t repair.”

Feed quality is top of the list. “If there is an issue, we need to know if it’s on the farm or just in the shed and rectify it quickly. It could be down to management rather than the feed itself. Good protocols and regular checks are key to safeguarding a good brood.”

An area where many can improve is in feed rates within the first 24 hours after hatch where advantages can be gained by adding an extra 40g of feed per bird, split over two feeds. The process of topping-up stimulates intakes and crop fill, and it also takes an early advantage of the birds’ natural curiosity to find and then to eat the feed.

He also emphasised the need to walk the shed. “‘Zig zag’ through the house and do a random check of groups of 10 birds within the first few hours after placement to assess crop fill. Note how many have feed or water only, or a mix of both. The target is 60% of birds to have a mixed crop fill at two hours and 80% at four hours.”

Observing chicks soon after placement will also identify any issues. “They should be evenly distributed with one third eating, one third drinking and one third resting or playing.

“If the shed is too cold, or too warm, bird distribution will be impacted and the chicks will not be feeding as readily, leading to suboptimal feeding and drinking levels.

“We want the birds to find feed and water instantly, and to establish good intakes. Feed form, particularly the use of the mini pellet, can make a positive impact here.”

Both temperature and humidity impact on air quality. “Humidity is really important, but it is so often overlooked in poultry sheds. Producers don’t consider what’s coming in and going out or take account of humidity – or CO2 levels inside.”

Humidity in the shed should average 55% and be below 65%. High humidity, particularly during the first few days, can have a detrimental effect on early chick growth. These young birds have a problem dissipating excess body heat.”

The use of temperature and humidity charts showing the ideal targets and monitors can easily be integrated into the management system.

Air pressure is equally important. The minimum air pressure requirement is 1.5 Pascals for every metre of shed width, so if the shed is 20 metres wide, the minimum air pressure required is 30 Pascals. This will enable the air to be conditioned before it reaches the birds.

Air circulation is another necessary component. “The air flow must be good and moving correctly through the house. Smoking the floor where the birds are, to check that there’s a good circulation of air, will confirm this.”

Air inlets are the most underrated equipment in broiler sheds, according to Daniels. “If they open equally and correctly, they can make a big difference. But they should be operated in line with air pressure and air volume requirements.

Recirculation fans, which are fitted and operated correctly and at the right time, are also beneficial and ensure a good uniformity of air movement,” he added.

A clean and well-delivered water supply can be prepared before the birds are placed. Water-quality checks should be made at the source and at end of the line, in the shed. “Too often, we find that pipes are dirty, or are old and need updating,” said Daniels.

“Also airlocks can be a massive problem just as birds are placed and it can end up with water everywhere. This causes issues with both crop fill and bird temperature, both of which have a big impact on their growth and performance. These issues are best sorted before the birds arrive.”

He also pointed out that these young birds need waterlines positioned at the right height and at the right flow for their weight. “Positioning too high or too low are common problems that I see. They should be correctly set at eyeline and a good neck stretch, primed and ready to deliver a water supply at the right pressure.”

Pre-heating the shed is essential too. “It takes at least two days to get the cement warm enough,” he added. “We’re looking for the floor temperature to be at least 28°C, the shavings to be 30°C, and an air temperature of 32°C.

“And the difference in cement temperature between the warmest and coolest areas of the shed should be less than 3°C.”

He warned against taking short-cuts with preheating. “I’ve seen situations where there’s a difference of 7°C in different areas of the shed. Warm chicks, those in optimal temperature areas, feed well and thrive, whereas cold chicks will be inactive, their target feed intakes will not be achieved, and their development is affected. This has a negative impact on long-term flock performance.”

Another area of concern is inconsistent lighting, where uniformity of light across a shed is more important than the LUX reading. “Contrast, when regulating dark and light periods in the 24 hours, is important for bird welfare and a difference of less than 30% between the brightest and darkest spots is ideal.”

A good brood is multi-factorial. “How you manage birds and their environment is key to getting them off to the best start, and success is usually reflected in the end performance of the flock. So if there’s a time to invest in the birds then it’s during the first six to eight hours of placement,” added Daniels.