Innovation and research is moving at a ferocious pace, we take a look at what options are available to farmers

Probably no type of innovation is currently affecting agriculture as much as digitisation. Robots, sensors, data clouds, and networked management systems already support farmers in their daily care of the health and welfare of their livestock, and new developments are happening all the time.

By 2025, it’s anticipated that the agricultural technology sector will be worth more than £136 billion globally. This includes over £129bn in the autonomous farm equipment market and over £7bn in the precision farming market. Just last month, a multimillion-pound hub for the development, testing and sharing of technologies to boost productivity in farming and the food supply chain opened in The Midlands.

The £4.4 million Agri-EPI Centre research & development facility is a joint project between government and Harper Adams University. Located on the university’s campus in Shropshire, the hub will bring together researchers, technology and engineering companies, food businesses and farmers. A priority for the new hub is to encourage farmers to use innovative technologies that could benefit UK agriculture – in turn, experts will explore how robotics, lasers, sensors and satellite technology could benefit farmers.

The market for futuristic innovations is changing fast, with new creations outpacing the old and innovations that recently were considered cutting edge, being quickly improved upon. In the future, virtual advisors are likely to become more common, assessing the data available from the flock and coming up with conclusions.

There is already a range of software and products on the market offering farmers data analysis and advice. One such product is OPTIfarm, a remote monitoring service specialising in the broiler industry, launched last year. The service monitors a flock 24 hours per day, offering advice on optimising performance, improved animal welfare, reducing antibiotic use and reducing insurance premiums. The service currently remotely monitors and controls poultry houses in the UK and across the world from its head office in Chesterfield and is working with clients in countries including Germany, Italy, Australia and Peru. The company is able to wirelessly interpret data from a number of different platforms.

These systems will become increasingly important, believes Detlef May, from the Institute for Animal Breeding and Animal Husbandry, in Brandenburg. “All important production parameters can be retrieved from almost any location in a short time,” he says. This is helpful for farmers. “But only the interpretation by the farmer makes data into practical knowledge,” he adds. For farm managers and their employees, “a sufficient affinity to modern IT is indispensable,” making it far easier to undertake routine tasks. And if those routine tasks are proving challenging, there’s also an increasing array of robots being developed, aiming to make the life of the farmer easier than every before.

At EuroTier, the world’s biggest trade fair for animal production in Hannover last November, a variety of new robots were presented for the first time, aiming to alter traditional production processes and supply chains, and making businesses more competitive than ever.

Sentinel, developed by Inateco is a mobile litter spreading system for poultry houses installed on the ceiling, which sprays litter around the barn, using visual and thermal sensors to specifically spread litter in areas with damp manure. This means the litter is only used where it’s necessary and there is less wastage. Sentinel can be installed in most ceilings without reinforcements. It acts within an area of 200 metres and is pneumatically supplied with litter materials via a supply hose – these can be shredded material, pellets, chips or meal. In addition to the visual and thermal sensors important for navigation, additional sensors for measuring carbon dioxide or ammonia content in the poultry house can be installed.

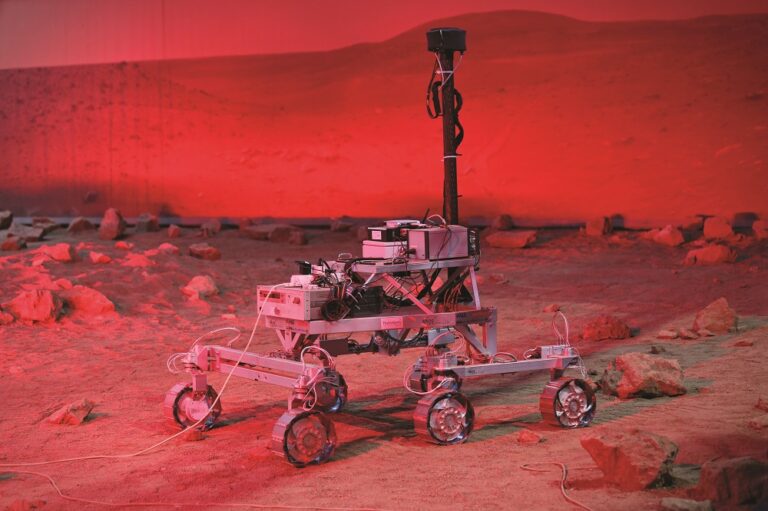

This means the robot can gather information from all corners of the poultry house, and feed back information to the farmer about how to improve climate management. Another new firm in this market is Thrive MV, from Shropshire, which is working in conjunction with the European Space Agency to adapt the Mars Rover robot for use in poultry sheds.

Chief executive Claire Lewis and her business partner Imtiaz Shams are developing machine vision, a form of artificial intelligence that she claims will, within a year, be able to weigh chickens by sight. In addition, it will use environmental sensing information to feed back information on chicken health, welfare and performance. The weight data will assist the whole supply chain, because it means processors can better plan supply and demand, with data showing which shed is likely to reach the target weight first.

It could even improve consumer perceptions of animal welfare, Lewis says, because it could lead to improved audits and because data would be available every day it could “help reassure the customer the chicken is being reared in an environment it’s responding well to, so it’s a happy, healthy chicken.” Digital tools on farm are also able to more easily detect operational weaknesses and, in the medium-term, there are indications that many recurring processes will become automated.

The result of using all these digital technologies, according to the organisers of EuroTier, is that the farmer will become a more professionalised part of the supply chain. Using digital technologies on farms raises the question of who has access to the data? If farmers share data with suppliers and customers, there has to be a pay-off. What is clear is that digitisation in animal husbandry is not an aim in itself and must be used to help the whole chain get better at what it does.

ROBOTICS DEVELOPMENT

Digitisation on farms is also being supported with technology right the way through the supply chain. One of the latest developments in poultry processing is a new project called FlexCRAFT, which is aiming to develop intelligent robots for food processing.

The programme is being run by the Dutch Wageningen University & Research (WUR) in close co-operation with TU Eindhoven, TU Delft, University of Twente, and University of Amsterdam and has been awarded Dutch government funding of €2.7 million. The research is also being paid for by processing equipment company Marel Poultry and German poultry processor Celler Land, which have contributed €1.3 million. The firms said they were “aware that intelligent robots will take on a crucial role in the food industry in the near future”.

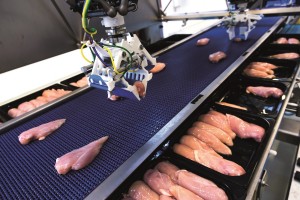

The WUR research programme will develop robots able to handle a wide variety of food products while taking into account the constantly changing environmental conditions and tasks typical for the agri-food chain. Marel has already introduced some robot technology to the poultry industry, with its RoboBatcher that batches breast and leg pieces into fixed-weight trays.

Other processes in the poultry value chain are, however, crying out for similar technology, such as planning, control, gripping and manipulation. FlexCRAFT will be able to provide particularly relevant support as one of its three cognitive robot projects will focus on poultry processing.

“We will be developing generic skills for robots to handle agrifood products of differing shapes, sizes and firmness,” says WUR programme leader professor Eldert van Henten. “Such actions may be simple for human beings but are tough challenges for robots. Robots need to understand the nature and condition of the food products they perceive and how to approach and treat them. Their sensors collect information, adding this information to their domain knowledge much in the same way as human beings build on their experience.”