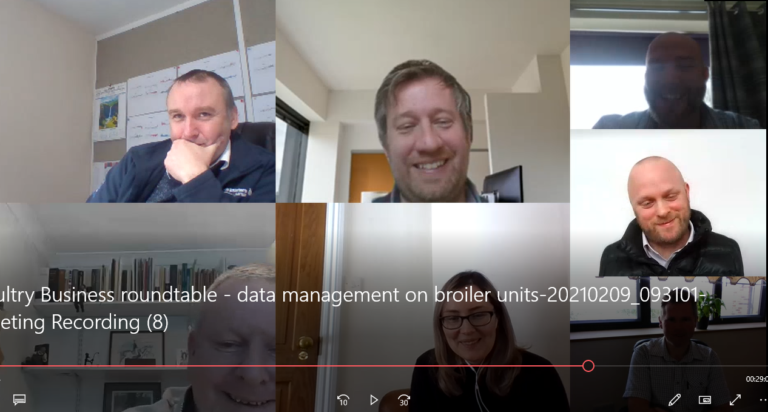

Poultry Business held a virtual round table discussion, sponsored by ForFarmers. Data management on broiler units was the topic, and PB editor Chloe Ryan was joined by a panel of experts and producers to discuss the challenges and opportunities, both on individual farms and right through the supply chain.

The panel, from top left, clockwise: Chris Chater, manager of central farming operations at Hook2Sisters; Phillip Hammond, partner at Crowshall Veterinary Services; Mark Brightmore, business support specialist at ForFarmers; Ian Dowsland, head of continuous improvement and research at Moy Park; George Adsetts, independent broiler producer, Chloe Ryan, editor Poultry Business; Andrew Fothergill, national poultry advisor, ForFarmers.

Poultry businesses capture a huge amount of data, but much of it is either ignored or not used effectively. “We in the poultry industry are excellent at gathering data, we’re not brilliant at actually using it,” said Andrew Fothergill, ForFarmers’ national poultry advisor. “The challenge is how do you turn data into knowledge or real information that’s useful?”

On broiler units, key indicators of bird health and commercial performance are routinely gathered: such as water and feed usage, temperatures and mortality. Within large integrators, data covering all parts of the chain from the feed mill, the hatchery, and the processing plant are recorded. Large factories monitor and record bird weights as well as welfare indicators such as hock burn and pododermatitis scores.

Unlike other agricultural sectors, which pay a levy to AHDB to collate data in an anonymised format and produce reports, the UK poultry sector has no central source of data that allows producers to benchmark their performance against the rest of the industry.

The panel discussed what data they capture and how they use it. Integrators such as Moy Park and 2 Sisters share data about farm performance between their farms to allow them to compare. “It is very much about driving performance to then dilute the fixed overhead costs,” said Ian Dowsland.

Hook2Sisters uses its data to keep track of commercial performance by calculating and monitoring “pence per square metre per week” generated by its broiler units, said Chris Chater. Data is used to calculate how well broiler units are performing, and poor crops are analysed to try and work out what went wrong.

As an independent producer, George Adsetts is reliant on data gathered on his three broiler units, rather than information shared by an integrator. His farms use Fancom systems, which capture feed and water usage, temperatures and ventilation in the sheds. He said he would welcome more data from the rest of the supply chain, such as information from the hatchery if there had been problems with chicks from a particular flock code.

The panel agreed that turning the data collected on farm into useable information was sometimes tricky. Different farms have embraced technology to different degrees. Moy Park installed a new central data system three years ago, said Dowsland, however some producers were still using paper charts alongside charts on their tablet or mobile device.

Adsetts still prefers to plot data himself, by hand. “This is probably still quite common industry practice,” he said. “We feel handwriting it out reinforces a lot of that data. If it is stuck at the back of a computer, it’ll sit there, and you could have massive fluctuations that nobody takes any notice of.”

Fothergill said one of the main problems with farm data was getting it in a format that was useful. Phillip Hammond agreed the challenge was often having the data in a format that was easy to interrogate. “There are farms even within integrators that don’t have that information on a computer and even if they do, they struggle with connectivity,” he said.

“The other issue is having the data in real time, because if we don’t, often it is too late to act. For example, if you had a disease problem, and you knew what real time FCR was by looking at feed intake and growth rate you could use that to make decisions on changes or interventions.”

Fothergill said ForFarmers was developing an app aligned to its Apollo nutrition range, which it hopes will help to present key data in an easily understandable format. “We are building on the simplicity of on the house pen card by developing an app which shows graphs for mortality trends, water consumption trends, so I or a vet have all that information to hand in real time. Then we can compare and contrast with other farms,” he said. “It is then that benchmarking becomes a possibility. It’s about taking a step back and using the data we already collect, better.”

“Real time data is key,” said Mark Brightmore, business support specialist for ForFarmers. “You go on to a farm and look at a pen card and it is quite difficult to quickly interpret the facts and figures, by collating the detail and showing in graph format we hope it will be easier to pinpoint a vaccination period that has knocked the birds, or a feed change, or a drop in water consumption related to a feed change. Things like that would be really useful.”

Lack of true information often leads to misleading assumptions, said Hammond. “If you record flock codes, you can see if you are trending higher in mortality on one flock code and compare growth rates with another flock code. At the moment you have a lot of hearsay on farms where you have people saying ‘oh you don’t want that flock code, it’s going to cause a problem’, but it might not be that at all. “It might just be that flock code is from a very big breeder farm so it is producing a lot more birds, so by default you are going to get a lot more problems. I think having the ability to analyse that data is key. There is a lot of data out there, but it is very poorly utilised.”

Some other countries have a more open approach across the whole supply chain. Dowsland said Denmark has an exceptionally open approach to data sharing. It is a relatively small industry, producing around 1.4 million birds per week. “Their data systems are government backed,” he said. “Producers put all their data in, feed suppliers put all their data in, hatcheries put all their data in, and it is there, visible for every single farmer to make the decisions they need to make, so who supplies their feed, who supplies their chicks, and it makes it really quite open and really quite competitive.”

In addition, Danish producers have government-funded bodies that offer advice and technical information. Although other panellists agreed data sharing could be helpful in the UK, there were concerns benchmarking could be used in a divisive way, as has happened when retailers made league tables for campylobacter. “League tables can be fairly regressive,” said Hammond. “I’ve seen hock and podo scores being used quite divisively.”

Chater agreed there was the potential to pit producers against each other in an unhelpful way. “What you’ve got to be careful of that you don’t get a feed conversion on one farm at 1.5 and another at 1.6 and then processors are not wanting to pay for that. There are always some natural variations; these are animals not tins of beans.” It is also important not to undermine producers in a way that will cause them to be turned off the whole industry. “I think we’ve got to be more positive with the people on the floor,” said Chater. “For me it’s about saying you’ve done a good job with what you’ve done, not saying ‘your hockmark is 25%’.”

The panel agreed that the role of data was ultimately to support stockmanship. It was crucial farmers were able to look after their animals, rather than spending time analysing data. “The key thing is the staff on the farm can actually manage their broilers,” added Hammond. “Their role is in managing the birds, gathering the data, and putting it into the hardware or software we provide them with, then having someone else analyse it.”

Chater said he was “incredibly nervous” about some of the implications of using data to automate processes on farm. “If technology is brought in, is it doing the job instead of the farmer? It could just create more headaches,” he said.

Dowsland said it was crucial the skill of the stockman was respected. “We’ve got to be really careful of technology. We’ve got to use technology to enhance stockmanship skills, rather than take away from them.”

A longer version of this article is available in the Poultry Business Feed & Nutrition supplement, available to subscribers either digitally via the website, or in the latest issue of the print magazine.