The UK may be the best in the Europe at controlling salmonella, but last autumn’s outbreak is a reminder that producers must stay vigilant.

Ever since the Lion Code was introduced, controlling salmonella has been a priority for British egg producers. Memories of the devastation caused by Edwina Currie’s ill-judged comments in 1988 that “most of the eggs in the UK are sadly infected with salmonella” is still fresh in the minds of those who lost their livelihoods when egg sales dropped 60% in a matter of weeks.

And largely, the efforts of the UK egg sector have paid off. The UK is the fourth largest European egg producer with 11.2% of all the laying hens but has the lowest instances of salmonella in the whole of Europe, at 0.1%.

However, it’s clear there is no room for complacency. Last autumn the Food Standards Agency (FSA) issued a recall after a salmonella outbreak that made over 100 people ill was traced to a packing centre in Kent.

Dave Hodson is from Rosehill Agricultural Trading in Shropshire, which works with 50% of the pullet layer market in the UK, including all rearing sites operated by Potters Poultry and Country Fresh Pullets.

Rosehill administers salmonella vaccines and audits rearing and laying sites to ensure all possible steps are being taken to reduce the risk of salmonella.

Free-range risk factor

The growth in demand for free-range eggs has increased the risk factor for salmonella. Regular access to wild birds increases risk. This makes biosecurity even more important.

“If you’ve been working with pigs that morning and you’ve failed to change your overalls or your boots, if there’s typhimurium in the pigs, it could be spread. The vaccine is fairly robust, but care should be taken,” says Hodson.

Red mite can play a part too. Red mite compromises the immune system and can put significant burden on the bird, increasing the risk of other diseases so controlling red mite is very important.

Vaccines

The first stage of salmonella prevention is properly administered live vaccines. Vaccinations contain the live strains of salmonella enteritidis and salmonella typhimurium. “Those two strains colonise the ovaries in the bird, but they are asymptomatic so you can’t tell if a bird has got it without testing,” says Hodson. “They can look perfectly healthy.”

“The benefit of live vaccines are they mimics the route of natural infection.” The vaccines are given via the water to pullets in rear at seven days, six weeks, and 14-16 weeks and that protects the bird for life, with some caveats.

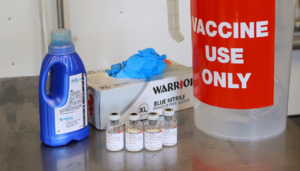

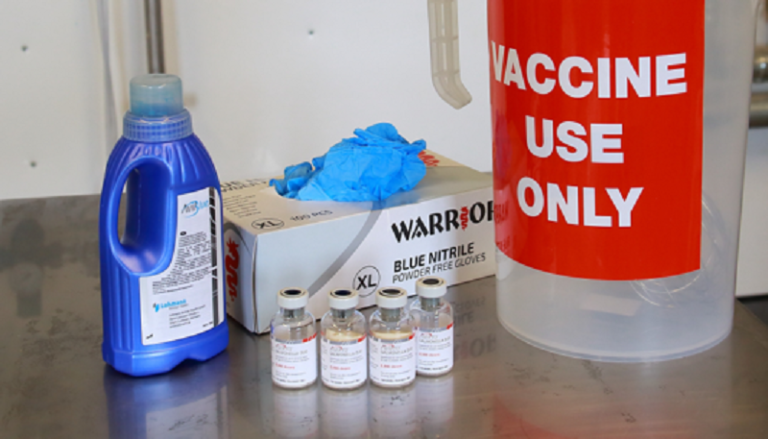

When Hodson visits sites, he ensures they have a properly working fridge to keep the vaccines at between 2 and 8 degrees.

While the vaccines are effective, any vaccine has the ability to be overwhelmed in poorly managed conditions, such as farms with high rodent populations, poorly disinfected housing, cross-contamination with other species such as free-range pigs, and poor biosecurity among workers and visitors.

This is why good pest control and biosecurity measures are essential.

Mice in particular are a risk factor for salmonella, says Hodson. “Mice have been shown to be a key driver in salmonella infections because they multiply rapidly and are constantly urinating and they will spread it around the site.

“A key part of the Lion Code is they are audited quite intensely in regard to their rodent control and biosecurity. Management does play a big part in controlling it and that is generally done well in the UK.

Training farm staff

Prior to the birds arriving on a site Hodson and his colleagues do a training session with the farm staff, and then when the birds come in, they once again go through the procedure for administering the vaccines.

“We go through storage, handling, make sure they are wearing gloves, and making sure their equipment is dedicated to vaccines only. The vaccines are being carried out at periods when the birds will be drinking more water because they are getting larger, so we tailor the amount of water to make sure the birds are all receiving an effective dose,” says Hodson.

The vaccines are combined with a water stabiliser. The water stabiliser prevents any chlorine or iron in the water from stopping the vaccination working. “We provide them with charts and it is very structured so we know exactly how much water they need to use. And then we physically show them what they need to do, which starts with draining all the water lines out.”

Once mixed, the vaccine is live for between two and three hours, and after that it ceases to be effective.

“A lot of care has to be taken and because it’s quite a long lived industry people can see how bad it gets when there is a salmonella outbreak like in the late 80s, so they’re aware of how important it is,” says Hodson.

“We make sure they mix it correctly; the birds have a period without water to make sure they drink. And the vaccine has a dye in it, so we make sure every single water line has the dye in it so when the birds are allowed to drink, they can only drink vaccinated solution.”

Applying vaccines properly while the bird is in rear is very important. “We carry out a lot of auditing to make sure that’s in place,” says Hodson. “We work with both Elanco and St David’s to train people in the use of Elanco vaccines and work with St David’s to make sure not only have they got the correct health plan in place, but to make sure all the vaccines have been applied properly so they are effective.”

Blood tests are taken from the birds between 10 and 13 weeks. Although it’s not possible to test for the effectiveness of the salmonella vaccine, it is possible test for the effectiveness of the Newcastle’s and the IB vaccines that are also administered. “Because they are far more delicate than the salmonella vaccine, we can then make a safe assumption that if they’re able to administer live vaccines that are very delicate then a good job will be done with the other vaccines,” says Hodson.

Preparing the house

Before pullets are transferred, the laying house has to be swabbed to ensure it is free from salmonella. “Salmonella can persist in the environment for a long time, especially in dust. So swabbing is done of all the walls, the floors, the equipment and sent off to a lab and that has to be clear,” says Hodson.

This ensures the pullets are going into a clean house. Then once the hens are housed, the first sampling done between 22 and 26 weeks of age. After that, the Lion Code stipulates testing is carried out every 15 weeks.

It’s clear management of a site is a very important variable. Cleaning and disinfection is crucial as well. Ensuring a site is completely clean on turnaround. Usually formaldehydes are used, which are effective at tackling salmonella and then also using proper biosecurity, so two-stage biosecurity on all Lion sites and all rearing sites. So an area where you have to dip your feet and change into overalls, then prior to entering where the birds are, put an extra layer of boot protectors on and then gloves to minimise any chance of infection.

Longer-lived birds

One topic that was raised at the last BFREPA conference in October 2019 was whether the trend towards keeping flocks longer could be compromising salmonella protection measures. Just a decade ago, flocks were finished at around 70 weeks. Now, due to better management of gut health and the widespread use of muck belts in the free-range houses rather than slatted systems, it has created a better, cleaner environment means flocks can be productive up to around the 80-week mark.

This has created some confusion around the efficacy of vaccines in older birds. What’s important to remember, says Hodson, is although most vaccines have only been trialled in birds up to 70 weeks, it doesn’t necessarily mean they become ineffective after that point. There is simply a lack of evidence beyond that age.

“It’s similar to caring for an older population like in an old people’s home,” he says. “When you get into 70 weeks and 80 weeks, the management of the site becomes very crucial, because any animal it’s immune system doesn’t operate as well as when it’s in its prime.

“So, if you’ve got a site that’s clean, free from mice and has good biosecurity, you are in a very safe place. If you’ve got a site with a large mouse population and biosecurity isn’t being rigorously adhered to, that opens the door for issues.”

What is salmonella?

There are about 2,300 serovars of salmonella. The main ones that concern the industry are enteritidis and typhimurium.

They are bacteria that colonises intestines, then they penetrate the intestines and go into the blood and then they infect the ovary duct, and then they infect the egg with salmonella.

If a bird is positive for enteritidis, not every egg will be positive with salmonella. In humans it causes acute gastrointestinal distress, such as diarrhoea and stomach cramps.

It doesn’t make the bird ill and it is not possible to identify it without testing. Measures such as vaccination and biosecurity have almost eliminated salmonella from UK poultry. But there is no room for complacency; that’s why testing is done frequently and why it’s so important.

The Edwina Currie effect

In 1988, MP Edwina Currie, who was a junior health minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government, made comments about the prevalence of salmonella in eggs that led to a dramatic drop off in egg sales and led to the collapse of her political career.

Currie told reporters: “Most of the egg production in this country, sadly, is now affected with salmonella.”

The effect was immediate. Egg consumption dropped 60% within a few weeks and four million hens were slaughtered.

“It led to bankruptcies and devastation and anyone who lived through that time it scarred them so much I think that’s why we are the best at what we do because they are determined it won’t happen again,” says Hodson.

Currie later said she had meant to say ‘much’ rather than ‘most’ but also defended her comments, arguing hundreds of people were becoming sick every week due to salmonella in eggs. However, she resigned from government two weeks later, after the British Egg Industry Council called her remarks “factually incorrect and highly irresponsible”, saying that the risk of an egg being infected with salmonella was less than 200 million to one.

In response, the BEIC developed the Lion Code, and auditing became rigorous and the use of live vaccines were incorporated, which proved to be very effective. Because rodents played such a big part in the spread of salmonella, auditing was put in place to check controls were being carried out. It was shown on sites with high rodent populations that by eliminating rodents the salmonella could also be eliminated.

Previous ArticleNI farmers lobby government on tariff policy

Next Article A sector in good health

Chloe Ryan

Editor of Poultry Business, Chloe has spent the past decade writing about the food industry from farming, through manufacturing, retail and foodservice. When not working, dog walking and reading biographies are her favourite hobbies.