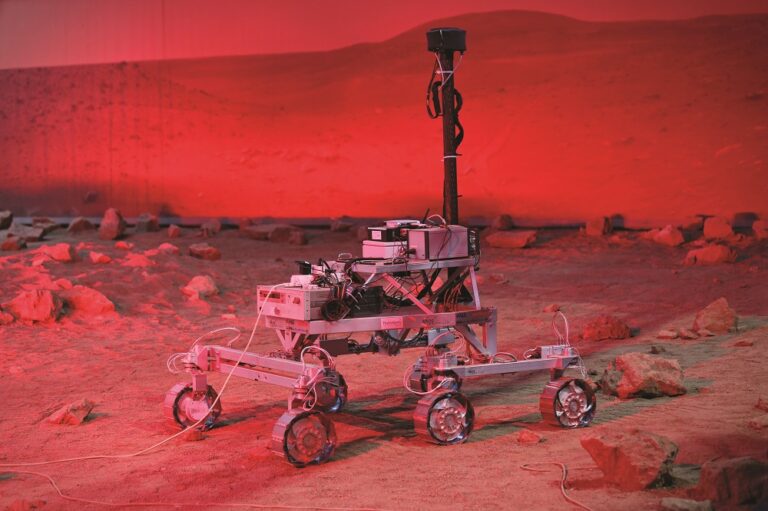

A start-up business from Shropshire has secured £40,000 in funding from the European Space Agency to adapt its Mars Rover robot – made famous by its mission to explore the surface of the red plane – for chicken sheds.

If that sounds almost absurdly far-fetched, that’s not the half of it. Thrive MV, headed up by chief executive Claire Lewis and her business partner Imtiaz Shams, is developing machine vision, a form of artificial intelligence that she claims within a year will be able to weigh chickens by sight. In addition, it will use environmental sensing information to feed back information on chicken health, welfare and performance to the farmer.

This will enable the adapted Rover to trawl chicken sheds, and report back weights to farm managers, which will then enable them to more accurately understand feed conversion ratio plan with processors when the birds will be ready to be caught. Lewis says the robot will be able to weigh around 90% of the population of a 50,000 bird shed in three days, providing a far more accurate picture than is currently available through either manual weighing or automatic scales dotted through the sheds that a sample of birds will walk over during the course of the day.

Thrive is testing its technology in six sheds on 350,000 birds. It is collecting bird weight data and imagery to train its machine vision, and then combining this with environmental sensor information and artificial intelligence.

This will enable the robot to look at birds through its cameras and immediately report back the weight, as well as collect environmental sensor information such as ammonia levels or faulty lights, and report back useful information to the farmer and other parties in the supply chain. Lewis says it will be ready to go in 2019.

Chance meeting

For Lewis, the journey from idea to reality has been remarkably swift. Just 16 months ago she was still working at Sainsbury’s, creating and implementing their agricultural data strategy, matching up what the customer wants and translating that into what it looks like on farm. After graduating from Harper Adams, Lewis also previously worked for AB Sustain analysing data from thousands of farms.

After deciding to set up her own business as a consultant, she attended the Cereals show last year to network and drum up business. It was there she had a chance meeting that would change everything.

At the show a team from the ESA was demonstrating the Rover. She started talking to them and the ideas started flowing.

“Through that link I met with my now co-founders and said I think you could use the robot in these ways,” says Lewis. “Currently chicken shed information is collected with hand held devices and there is a biosecurity risk, so what if we could just load your robot with all these things, a weigh scale, a sensor and start to put information together? So, we discussed it a bit more and then we set up Thrive and we are currently developing the technology to do all these things.

“We did the assessment of the market, spoke to farmers to understand what it does deliver, and started to get to the point of not being limited by what is available today but what is the art of the possible.”

As well as co-founder Inteav Shands, Thrive is made up of Luke Robinson and James Arthur. Robinson is a world class expert in artificial intelligence, machine vision, and Arthur’s field is tech software and business development.

Since then they have worked hard to create more networks in the poultry sector, with farmers, advisers, and farm technical experts from Alltech, all coming in on the project. Andrew Maunder, of the Lloyd Maunder butchery group has come in as chair. Thrive also has the backing of the RSPCA, which has come on board through its Freedom Foods scheme to support the work.

They are also working hard to develop the technology. “Certain things we’re going to create from scratch, such as weighing the chicken through imagery, machine vision, then there are other things you can pick off the shelf, because there are already some effective solutions out there,” says Lewis.

Poultry partners

The firm has taken the strategic decision to avoid working directly or exclusively with any of the big processors and supermarkets while the technology is in its infancy, because Lewis wants to make the product attractive and available to all parties when it’s fully developed.

“My view having been in the agri-food sector you need to help as many people as possible because farming is tough, and margins are thin everywhere in the supply chain. The beauty of what we’re doing is the information we’re collecting is directly of benefit to farmers, it will tell them what to do in their sheds and autocontrol some of these features, whilst also being able to direct activity and say ok in that part of the shed the light is flickering we need to go and sort it out now.

“And then there is weight data and health and welfare metrics,” she adds. “Weight data feeds into supply chain planning for processors, so seeing which shed is growing more or less to feed into which pipeline, so they can better align supply and demand.”

It could even improve consumer perceptions of animal welfare, she says, because it could lead to improved audits, because data would be available every day, which could “help reassure the customer the chicken is being reared in an environment it’s responding well to, so it’s a happy, healthy chicken.”

Funding

Thrive secured its £40,000 in funding through the ESA, which each year allocates funding to businesses that want to use space tech and apply it to different sectors.

“It’s an incubation programme,” explains Lewis. “They provide you with guidance, be it business modelling, how to make an investor pitch, and they support organisations that use space technology. They also provide networking.” In return, Thrive has to report back on progress quarterly.

Lewis points out space technology is very well suited to agricultural applications. “It’s really robust, it’s often really sensitive and it’s used to toxic environments so it’s highly suitable for agriculture.”

This month, Thrive will start pitching to venture capitalists to try and secure additional money to fund the next stage of the process.

Competition?

Currently there is no absolute direct competition, although there are several other robots either in the market or in development aimed at the poultry sector. There’s Tibot Rover, which encourages chickens to move around the shed, and another one being developed by Wageningen University, which picks up eggs. Lewis finds these developments encouraging, “because we know Rovers are accepted by chickens and it doesn’t throw them into chaos!”

Looking into the future

Lewis acknowledges some people get nervous at the pace of change, particularly when it involves artificial intelligence. But she is keen to emphasise how Thrive’s work is grounded in what is practical and useful for farmers and the industry. And she should know. She grew up on a beef, dairy and sheep farm in Cheshire.

“It’s so exciting,” says Lewis. “I am emotionally attached to farming, and I get a bit scared by the complete roboticisation, but it’s developing the tech that is going to help farming in the right way.

“The stockperson can’t be in the shed all the time,” she points out. “And when we have things like avian influenza, it’s limited who can go in the shed. So hopefully by having a discrete robot going around doing these tasks saying you absolutely need to be in this shed to sort out this lightbulb, or your vent is broken, you can really be targeted with your time.”

There is a lot of uncertainly over how technology such as this will shape the face of farming in the decades to come. But for now, it’s exciting to watch the pace of change, albeit with some reservations.